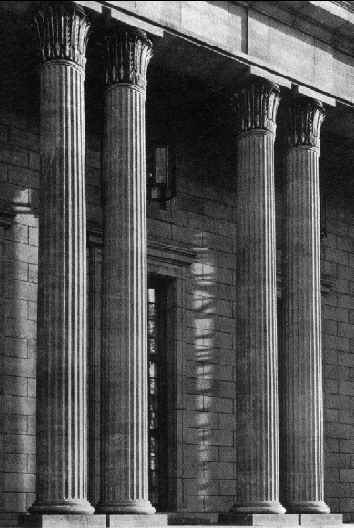

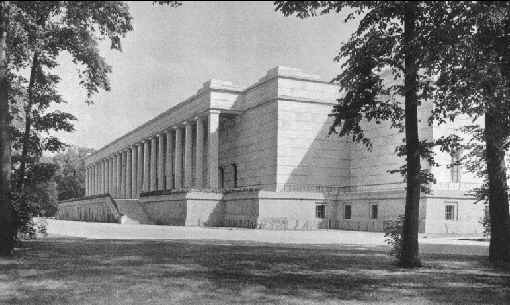

Architect: Albert Speer, Colonnade of the garden facade of the Chancellery. 1 |

Architecture in the Third Reich

Architect: Albert Speer, Colonnade of the garden facade of the Chancellery. 1 |

Hitler was obsessed with art during his whole life. His early life had seen his rejection by the Academy’s painting class in Austria. He then switched to seeking admission to the Academy’s architecture school which he later declared, was his real love. Again he was refused admission due to the fact that he had not graduated from high school. These early failures cut him deeply and in a sense his entire career can be seen as a single attempt to prove him and to the world that the Academia's were wrong, that he was a superbly talented architect.2

Hitler hated modern architecture and he persecuted the modern architect.3 New Architect was declared ‘UN-German’4 and architects who reject the "Principles of the F�hrer" began to emigrate from the Third Reich.5

One of the principal targets of the avant-garde art was the Bauhaus ("House of Building"). Hitler had been a mediocre academic painter since youth, and had developed an intense hatred of the avant-garde. Hence, when Hitler came to power in 1933, the Bauhaus was closed for good. A number of the artists, designers and architects who had been on its faculty emigrated to the United States, including Albers, Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. Other architects who left include Karl Mey. Erich Mendelsohn Otto Wagner and Bruno Taut.6

Hitler was attracted to the classical architecture of the ancient Roman Empire because he believed the Romans served as models for the Germans and because he believed in a racial tie linking the Greeks and Romans with the Nordic race of Germans. He greatly admired Paul Ludwig’s neoclassical design for the House of German Art in Munich, which corresponded to his own preconceived ideas about representative architecture. By the end of 1933, Hitler had endorsed Troost’s neoclassicism as the appropriate style for the architecture expressly intended to represent the Nazi State. Neoclassical buildings were to embody physically the great strength and will of the party, the state, the nation, the German people, and their F�hrer.7

Hitler had been known for his direct intervention in architectural matters. Every important architectural project fell under the scrutiny of this failed architect.8 He set forth programmatic outlines, contributed his own sketches, chose architects, did modifications9, personally laid the foundation stones of important buildings, and in speeches on the occasion of their opening he never missed a chance to develop his ideas about the enormous role of architecture in the spiritual life of the people.10 Furthermore, the Nazis launched a propaganda campaign asserting that their buildings, particularly the monumental neoclassic buildings of the state did indeed represent a unique style; they claimed that the "stones" of these buildings spoke the "word" of the movement.

Actually, neoclassicism was widespread at this time. In Germany, there were examples from earlier regimes. Albert Speer placed his own work in the tradition of late eighteenth century --- and early nineteenth-century Prussian neoclassicism, particularly the work of Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Friedrich Gilly. Moreover, monumental neoclassicism was hardly unique to Germany. One could find neoclassical government buildings, exhibition halls, museums, schools, banks and theaters all over in Europe and in America as well. At the same time that Hitler planned to embellish the capital city of the Third Reich with neoclassical monuments, in Washington the Americans built the neoclassical National Gallery, Supreme Court and Jefferson Memorial to enhance the neoclassicism of the Capitol Building and the White House.

Be that as it may, monumental neoclassicism was trumpeted by Nazi propagandists as the great contribution of their movement to a revival of German culture. They successfully convinced both their supporters and their enemies that monumental neoclassicism embodied Nazism and that a distinctly National Socialist architecture broke from and rejected previous architectural traditions. Furthermore, in the great Nazi architectural projects, architecture and urban design were expressly political ideological. Buildings, however, were not to be simply symbols of Nazism. Individual buildings and complexes of buildings were to be functional, serving as administrative centers, locations for ceremonial display, meeting halls, parade grounds, train stations, and the like, while simultaneously impressing those who worked there and those who visited with the great power of the regime and with their own powerlessness as individual citizens. Hitler equated functionality with beauty. Indeed, at one point he declared that "the final measure of beauty was a crystal-clear accomplished functionality." Hitler also equated power with size. He remarked: "Only through such might works one give a people the consciousness of being the equals of any other great country, even America." 11

Everything large and impressive found favor with him. Rome’s colosseum, basilica of Saint Peter and Pantheon were for him the best examples of monumental buildings, an architecture produced by the community. These and the Madeleine in Paris, and especially the dome of Lev Invalides, inspired his building plans for Berlin. In addition, the colossal scale also resulted from the desire to have huge masses of people experience a collective identification with the spirit of the buildings.12

Hitler’s plans for large national buildings dated from the early twenties. As soon as he was in power in 1933, he began to realize some of these projects: in Munich, the Bruunes Haus, the layout of the K�nisplatz, and two large Party Buildings, the F�hrer Building and the Administration Building of the NSDAP. In October of the same year, he also laid the foundation stone for a new House of German Art, in Munich. For Berlin too, he began to initiate plans he had devised in the 1920s.

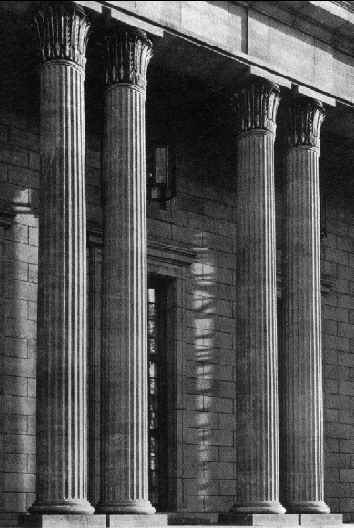

Architect: Paul Ludwig Troost, F�hrer Building. 13 |

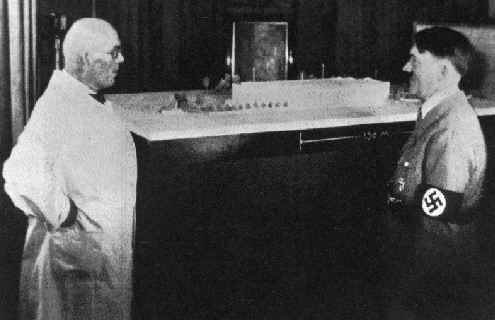

His love for architecture explains why he left the architects alone, and bowed to their professional experience. He gathered around him a group of efficient pliable architects able to realize his dreams: Paul Ludwig Troost, Albert Speer, Hermann Giesler, and Fritz Todt. Hitler considered Troost the greatest German architect since the nineteenth century Neoclassicist Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Theirs was a kind of pupil-master relationship. After Troost’s death, Hitler even toyed with the idea of taking over his architectural practice.

Hitler and Troost with the model of the House of German Art.14 |

Architecture became the most forceful expression of the National Socialist idea: Here "the word had become stone" in order to express true German greatness. "Philosophy is more invisible in architecture than in any other art form… The buildings of the F�hrer are the signs of the philosophical change of our time. They are National Socialism incarnate… Hitler formed in these buildings the noblest qualities of his people… The greatness of the German soul eternalized in stone, witnesses of heroism… they are the holy shrines of our people. Their destiny is to proclaim our philosophy." 15

In the 1934 Reichsbank competition, which invited designers from all points in the architectural spectrum for the new Reichsbank headquarters, Hitler personally intervened into the outcome. The end of open architectural competitions coincided with the rise of the Reichskulturkammer (Reich Chamber of Culture), the party organization responsible for all the arts. As Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels explained in November 1933: "In future only those who are members of a Chamber are allowed to be productive in our cultural life. Membership is open only to those who fulfill the entrance condition. In this way, all unwanted and damaging elements have been excluded." This intention became statue in the Architects’ Law of October 1934, which specified that only members of the Reichskammer der Bildenden K�nste (Reich Center of Creative Arts) could use the title of architect, the section responsible for architecture and visual art. This political pressure brought many architects to the Nazi’s cause.

With absolute power over the architectural profession focused at the center, one would expect the emergence of a coherent design philosophy. This was not the case. National Socialist ideas about architecture, like those about the visual arts, were after contradictory.

The enormous difficulties experienced by historians in their attempts to establish coherent patterns in the National Socialist ideology are a reflection of the Nazi state itself, which, as William Carr has noted, "was no monolith but a mosaic of conflicting authorities bearing more resemblance to feudal state, where great vassals were engaged in a ruthless power struggle to capture the person of the king who in his turn maintained his authority by playing one great lord off against another."

In this context, conventional oppositions such as Modernist and traditionalist make little sense, as both tendencies were constantly present in the party ideology as essential counterweights in the balancing act performed by Hitler. As research has indicated, some of the leading figures in the party, such as Robert Ley, Fritz Todt and Albert Speer were essentially modern in their thinking and in their policies, while others, such as Heinrich Himmler, Walter Darre and Alfred Rosenberg, had a mystical attachment to the German Soil and to the whole apparatus of Blood and Soil.

The technocrats had visions of a Modernist National Socialist State, almost American in its commitment to technology and industrial rationalization, while the anti-Modernists dreamed of rebuilding German superiority through the labors and ethics of the German peasant. In his necessary ambiguous position in the center, Hitler gave some encouragement to both groups but identifies solely neither.16

What soon united National Socialist views on architecture was the rejection of a modern style. A quaint vernacular style for housing and a monumental style for public buildings became the order of the day. "In the future there will be no more ‘boxes for living,’ no churches that look like greenhouses. No glass house on top of columns… built as a result of professional incompetence. No prison camps parading as workers’ homes subsidized by public money. Get compensation money from those criminals who enriched themselves with these crimes against national culture," wrote the infamous Bettina Feistel-Rohmeder, castigating the modern Siedlungen (multiple-dwelling complexes) of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Bruno Taut, and other representatives of the modern movement.17

When the Nazis came to power, they began the task of reshaping Berlin in a form more congenial to the new regime; a task entrusted in January 1937 not to the established planning authorities, but to a new office, the General-Bauinspektion (GBI), directed by a young inexperienced architect, Albert Speer.

Working on the basis of guidelines and formal motifs devised by Hitler himself – the giant axis, the domed hall and the triumphal arch – Speer’s vision for Berlin was both megalomaniac in its scale and very simple in its basic strategy. Two axes were to be established, running north-south and east-west. These would cross just to the south of a giant new square flanked by the existing Reichstag, a vast domed hall, the F�hrer’s Palace, and the Armed Forces High Command. At their extremities, the axes were planned to linked with the outer autobahn ring, with a further four inner ring roads to provide concentric circulation.

The central section of the north-south axis was conceived as a vast parade route, designed to house the principal public buildings, ministries and commercial offices of the new Reich on the boulevard 5 kilometers long and 120 meters wide. Although large-scale demolition and site clearance was undertaken, little was actually built, and the north-south axis remains a paper monument to the megalomania of the Hitler’s Reich.18

In the same year the two new Party buildings were built. Troost had chosen a neoclassical style, which was to echo the older buildings on the other side of the square. "Pillars have again become an important element; they are not, as in the seventeenth and eighteenth, mere decorative elements but are an integral part of the architecture. The ‘spirit of the Gothic’ which lives in the German character, with its emphasis on the vertical, has been married to Greek horizontal harmony. Verticality and the horizontal share the rein."

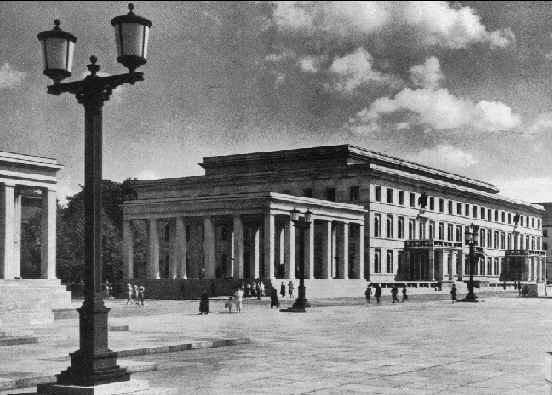

Munich became the capital of the arts also. In order to demonstrate publicly the importance he gave to the city, Hitler began, in his first year, to plan for a new art gallery, a House of German Art. Troost was again the chosen architect. Hitler laid the foundation stone in October 1933 on the first Day of Art.

Troost did not live to see his new House of German Art completed. The work was finished by Leonhard Gall and Troost’s widow, Gerdy. Hitler also took an active part in this project. It was a neoclassical structure, a heavier version of Schinkel’s Old Museum in Berlin (1823-30). Constructed of the same stone as the Regensburg Walhalla and the Kelheim Befreiungshalle, the House of German Art took its place self-consciously in German tradition.

Architect: Paul Ludwig Troost, House of German Art. 19 |

The building was gargantuan in scale; the portico measured almost 575 feet in length. Two large braziers stood on a pylon at each end of the fa�ade. It was praised as a "Temple of German Art, one of the new monuments of a new time," and indeed the temple form announced a noble art, reaching back to antiquity. Hitler said of it: "The building is as notable for its beauty as it is for the efficiency of its services… but it a temple of art, not a factory… the result is a house fit to shelter the highest achievements of art and to show them to the German people." Here the nation was to display the most notable and heroic in art. As usual, it was built using the latest engineering techniques, including a complex air-conditioning system and an air-raid shelter.

Several more buildings were built in the new style, most notably the House of German Law designed by Oswald Bieber, and the House of German Medicine, designed by Roderich Fick.

Architect: Oswald Bieber, House of German Law. 20 |

Nuremberg was, until its destruction in World War II, one of the best preserved medieval cities in Germany. Its appropriateness to Hitler’s of patriotism was obvious. It was here that Hitler planned his giant meeting sites. The existing sports field was enlarged to five times its original size, and a huge area of over 11 miles, the size of a small town.

The Olympic Stadium was more than a mere sports arena. It was designed as a huge assembly place for hundreds of thousands to celebrate Nazi rituals and experience group exhilaration. It was a place where the spectator would become a participant. The monumental square in front of the main entrance to the stadium, which consisted of a massive paved concourse flanked by flagposts, spelled out the importance of the stadium as a great meeting place for Germans.

Architect:Albert Speer, Olympic Stadium. 21 |

There was to be a Great Hall known as the Kuppelhalle (" Kuppel" means dome) on account of the huge domed hall with a seating capacity of 180,000. The cupola, based on a drawing by Hitler from 1925, would rise 1,050 feet. The outside of the cupola was to be covered in patinated copper. It was crowned by a 100 foot-high Eagle of the Reich grasping the world in its talons, symbolizing Hitler’s role as ruler of the world.22

Architect: Albert Speer (after drawings by Hitler), Model for the Great Hall.23 |

Of the architecture of the Third Reich – fascist monumentalism expressing megalomaniac claims and ideas- it can only be said that just a small part of what was planned was implemented, and most of what was realized was destroyed again during the war. The Nazis drew on antiquity and Schinkel, but they perverted the classical tradition with their colossal and oppressive structures.24 As what Albert Speer, the chief architect of the Third Reich, concluded after many years: " There was no ‘F�hrer’s style’, for all that the party press expatiated on this subject. What was branded as the official architecture of the Reich was only the neoclassicism transmitted by Troost." This statement corresponds to a now widely held view, which it may in fact have helped to establish.25

(London:George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd, 1992). p. 123.