Ideal Music

The Portrait of Richard Wagner (1813-1883) 1

The parameters used by the Nazis to define the ideal form of music was more haphazard in comparison to their justifications for attacks on degenerate music. As mentioned in the introduction, unless the music is closely allied to an unequivocal political slogan, Nazi cultural aesthetics found great difficulty in determining the meaning and value of a particular piece of music.2 In this regard, individual pieces of music, especially serious music, was sometimes given different treatment in terms of recognition and condemnation, and political approval and rejection. However, the condemnation and purging of degenerate music was done with apparent unity and vitality.3

In fact, any music could be considered ideal and acceptable to the Nazis if the following conditions were met. The musician had to be an Aryan; a non-communist; not sympathetic to the Weimar Republic because the Weimar Republic was made responsible for the growth of avant-garde music making, and the Nazi detested the aloofness of these modern music; jazz and polka were considered racially inferior music, and most importantly, the musician himself must not be a Jew and/or the music itself should not be composed by a Jew.4

Richard Wagner's operas operas popularised the German mythology; the image of a Teutonic Siegfried (see section on Origin of National Socialism). Wagner's operas have almost all the elements that the Nazis craved for to help bring back the v�lkisch spirit among the German people. The spirit of the woods, the ever victorious warrior such as Siegfried, and most importantly, the heroes and heroines in Wagner's operas are always represented by blond, Teutonic Aryan (see pictures below). To Wagner, music had to be "rooted in folk and native tradition in order to be a genuine expression of the national community it would thus help to revitalise".5

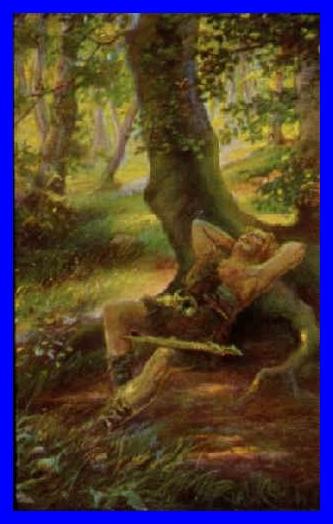

This picture shows Siegfried lying in the "mythical" forest. This picture could be almost considered perfect by the Nazis. A big, blond hero lying in the forest where the Germanic spirit (Volk) could be found. 6 |

This painting, taken from the Neuswanstein Castle, depicts a scene in Wagner's opera Tannh�user.7 |

What the Nazis wanted was an art (music) that confirmed and elevated German nature, native tradition, and the sociopolitical order it served.8 These were idealistic features of National Socialism, who customarily associated themselves with the v�lkisch movement.

Besides Wagner, other serious music composers of the past and present such as Beethoven, Bach, Mozart and the then contemporary Richard Strauss were added to the rank of Wagner to represent the ideal form of music and maybe to even help restore the lost v�lkisch spirit in the German people.

It is not enough to recognise and draw a line somewhere in defining what was politically acceptable ideal music. Such form of music had to be promoted. The establishment of the Reichmusikkammer (National Music Chamber) was for the purpose of creating a comprehensive and coherent music policy and to bring music to the ordinary people through the Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) movement.