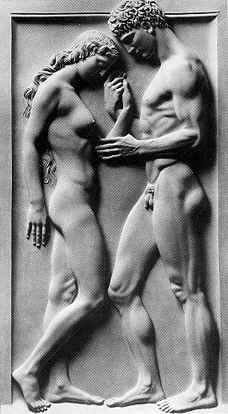

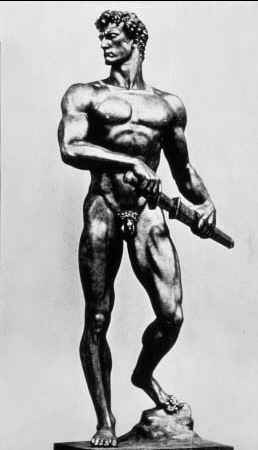

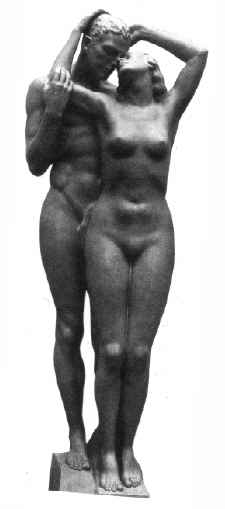

Arno Breker, You and Me. 3 |

Ideal Visual Arts - Sculpture

In comparison to paintings, sculpture seemed better able to express the National Socialist obsession with race and biology.1 What paintings could not express was made up for by sculpture. Sculpture offered a body language that people could identify with and on which they could model themselves. Sculpture was the close to living examples of what an Aryan would be like physically. The sculpture of Arno Breker drive home this message both vividly and strongly.

Sculptor had very special roles to play in the Third Reich. The sculptor's natural domain, the human figure, was a medium admirably suited for the solid manifestation of the National Socialist ideal of the human form.2

Arno Breker, You and Me. 3 |

| "It was the task of German art

to consolidate the racial structure of the German people as the ultimate fulfillment of

the Greco-Nordic tradition. The new period today is working on a new type of human being. Tremendous efforts are being made in countless fields of life to elevate the people, to make our men, boys, youths, the maidens and the women, healthier and thereby stronger and more beautiful. And from this strength and this beauty pours forth a new feeling of life! Never was humanity in its appearance and its feeling closer to classical antiquity than today. Competitive sports and combat games are hardening millions of youthful bodies and they show us them now rising up in a form and condition that have not been seen, perhaps have not been thought of, in possibly a thousand years . . . This human type which we saw appearing before all the world at last year's Olympic games in its shining, proud, physical strength and beauty, this human type is the type of the new time." Adolf Hitler, 1937 4 |

As sculpture has three-dimensional effects, it was obvious to the National Socialist that the sculptor could render this new human type in monumental proportions and in durable stone and bronze. Sculptures therefore served quite well in advancing the National Socialists' ideology, which was the existence of the superior German race, the blond Aryan. This blond Aryan was often stereotypically depicted as strong, youthful, with blond hair, and blue eyes.5

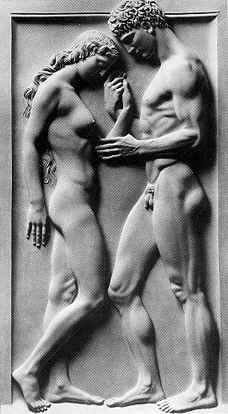

Arno Breker, Readiness, 1937. 6 |

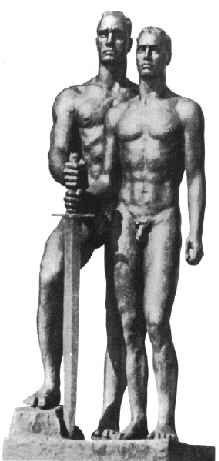

Georg Kolbe, Commemorative Memorial. 1935. 7 |

Breker, the leading sculptor in the Third Reich understood the requirements and messages for the National Socialist very well. In addition, there were Professor Josef Thorak and Georg Kolbe whose works depicting the typical Aryan lent credit to the National Socialist and were very much sought after by the National Socialists.8 However, these sculptors were not considered first class by Lucie-Smith who wrote that Breker was certainly not a first rate sculptor and Lehmann-Haupt seconds that. Nevertheless, he was commissioned by the National Socialists to produce sculptures based on the National Socialist ideal and Breker's willingness to succumb to such demand. Breker's service was definitely not sought because he had immeasurable talent.9 Even if these sculptors had talent, they abdicated it in favour of the National Socialist requirements. This not doubt dealt a great deal of damage to the standard of sculpture in the Third Reich.

The Roles of Sculpture

The National Socialist were quick to recognise that the traditional role of sculpture gave it power as political message carrier.10 Exploiting this, the National Socialists engaged sculptors, although not the first-rate ones, to make sculptures that carried National Socialist values and the inherited codes of the warrior or soldiers, war, the Party and comradeship. The themes were very much represented by the sculptures of Adolf von Hildebrand, Fritz Klimsch, Richard Scheibe, Georg Kolbe, Ernst Kunst, Robert Stieler, Arno Breker, Josef Thorak and along list of other sculptors.

Looking at these sculptures, it is not difficult to discover these works had strong classical Greek leaning. Other themes for the creation of sculptures were motherhood, the fertile female body, the peasant and the beauty of the nude figures. However, it was the beauty of the male body which dominated sculptural output.11 The idealised male body that showed mainly health and strength was heavily expounded upon. After all, the Reich needed the healthy and strong male soldiers in its ambitious military conquest and expansion overseas.

Richard Schiebe, Standing Female. 12 |

Josef Thorak, Couple. 13 |

The male nude was always tall and broad-shouldered with narrow hips. He represented the ideal of the Aryan race and the virtues of the regime: comradeship, discipline, obedience, steeliness, and courage.14 The important thing is that the sculpture not only postulated an ideal of beauty but an ideal of being. It was even said by Hitler, "If you have seen these works of art, you are bound to feel a nobler person".15

Sculpture was made to convince the German that they belonged to the superior race and only the superior race would possess such ideal "human" body.16

Although there were enormous numbers of sculptures produced and some were disproportionately large, the standards of sculpture did not make a breakthrough due to several reasons. One may be that the sculptors who were engaged by the National Socialists were not the best in the industry. Secondly, the limitation on themes for creation by the National Socialists had certainly limited the scope for creativity. And, it is ironic for both the sculptors and the National Socialists to equate largeness with greatness. On the whole, the steely cold and perfectly crafted male sculptures and female nudes without any suggestion of voluptuous sexuality were considered by George L Mosse as beauty without sensuality.17